Spectrum Shortages - Why it's happening and what can be done

by Jeff Foster

Sprint 4G Rollout Updates

Friday, April 20, 2012 - 11:31 AM MDT

Is there a "spectrum shortage?" Those two words send shivers down the spines of wireless industry executives. New services demand ever more spectrum, and, the story goes, there simply isn't enough spectrum available. An Internet search engine will easily find hundreds of thousands of links to the term "spectrum shortage." Many claim that it will be the downfall of America.

The dwindling availability of a finite resource that can't be seen or touched threatens to possibly disrupt the mobile lifestyle that virtually every American has embraced. Dropped cellphone calls, delayed text messages and choppy video streams could become more frequent occurrences because the airwaves on which that data travel are nearing capacity at a time when mobile usage shows no signs of slowing.

Federal regulators and industry players are searching for ways to fend off the supply-and-demand collision. Dish Network recently acquired a large block of vacant wireless spectrum that pending regulatory approval could be used for mobile broadband services.

Short-Term Plan

AT&T tried to merge with T-Mobile to solve its own capacity problem. It wanted to get its hands on T-Mobile spectrum. Still, that would have been only a temporary fix at best. Remember all the terrible stories about the quality of AT&T's wireless data network over the last few years? They say they simply don't have enough.

The reason is that during the last few years, smartphones like the Apple iPhone and the many devices running Android emerged, and wireless data traffic grew like crazy. This problem jumped up and bit AT&T in the rear end. Suddenly, so many people were sucking so much data that the network could not handle it, due to spectrum shortage. Spectrum is like the size of the hose, and a wider hose is needed to carry more data for more customers.

A couple good things are suddenly happening that may give carriers a little time to solve this increasing problem. Perhaps Verizon starting to sell the iPhone last spring has something to do with it. If so, then now with Sprint selling the iPhone, AT&T will have more breathing room, at least temporarily. That's the good news. However, that reprieve will only last a short while before the exploding smartphone and wireless data growth catches up. Then the other carriers will be faced with the same problem that's confronting AT&T.

In the first quarter of 2011, the amount of data the average smartphone user consumed each month grew by 89 percent to 435 megabytes from 230 MB during the same quarter in 2010, according to Nielsen research. That's up from about 90 MB in 2009. For reference, the average size of an MP3 music file is about 4 MB.

"Texting has always been traditionally viewed as a lightweight consumer of bandwidth, but if I start adding videos and pictures to my texts, that also starts consuming more bandwidth," said Tom Cullen, an executive vice president with Dish. But the primary growth driver will be video. Consumers can go through 5 gigabytes a month simply by streaming 10 minutes of standard definition video daily, he said.

Data use is skyrocketing

Data from the FCC indicate that more Americans are looking at their phones rather than talking on them. In 2009, 67 percent of available spectrum was utilized for voice and 33 percent for Internet data. Those percentages are now at 75 percent for data and 25 percent for voice. With each new iPhone release, data consumption grows. The iPhone 4S eats up twice as much data as the iPhone 4 and three times as much as the iPhone 3G, according to a study by network services firm Arieso. The new iPhone features Siri, a bandwidth-heavy voice recognition feature.

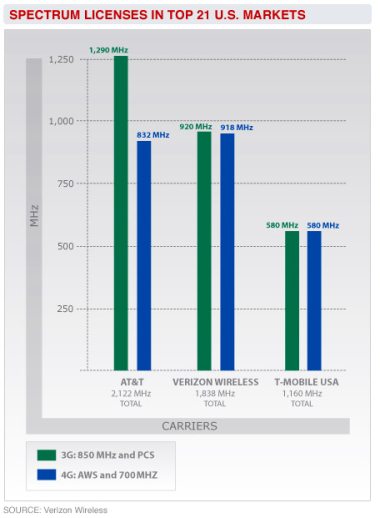

The FCC estimates the U.S. will face a spectrum deficit of 90 MHz in 2013 and 275 MHz in 2014. To address the crunch, the federal government hopes to unleash 500 MHz of spectrum currently used for other purposes for wireless broadband by 2020. To put that figure in perspective, there is currently 547 MHz of spectrum allocated for mobile services, and AT&T and Verizon each own about 90 MHz.

The government plans to hold so-called incentive auctions, which will try to lure spectrum owners such as TV broadcasters to sell their licenses. Verizon Wireless has agreed to purchase spectrum from a group of cable-TV companies. Sprint has expressed interest in working with Dish, which acquired the bulk of its 45 MHz of spectrum through two deals for bankrupt satellite technology companies. Dish chairman Charlie Ergen has said that the satellite-TV provider would prefer to partner with an existing wireless carrier on a high speed, 4G network. In response to recent comments by Sprint Chief Financial Officer Joe Euteneuer about the company's interest in working with Dish, Cullen said other wireless carriers are in the same situation. After failing to acquire T-Mobile, analysts expect AT&T to make a play for Dish, a long-rumored merger partner.

As for T-Mobile, perhaps the most logical buyer is CenturyLink. T-Mobile's German-based parent company has indicated that it might exit the U.S. market. CenturyLink, which acquired Denver-based Qwest last year, is the third-largest landline phone company but does not own a wireless service, unlike the top two, AT&T and Verizon.

Carriers are trying to offload as much traffic as they can to Wi-Fi networks, which ride on unlicensed spectrum. In some areas, they're installing picocells, which are smaller cell sites that can help boost capacity in dense areas.

Finally, they're spending billions of dollars on LTE networks that use the airwaves more efficiently. Verizon and AT&T already have 4G LTE networks in place, and Sprint is moving to the technology. Dish says it hopes to enter the mobile broadband market with advanced LTE technology by late 2014 or early 2015. If Dish were to also offer voice service, it would come through VoLTE, which is similar to Voice-over-Internet Protocol (VOIP) phone services. Dish still needs the FCC to drop a condition tied to its spectrum that requires devices to have the ability to communicate with satellites, not just ground-based cell sites. The rule-making process that will likely remove the requirement is underway and could be completed by summer's end.

Is there really a shortage problem?

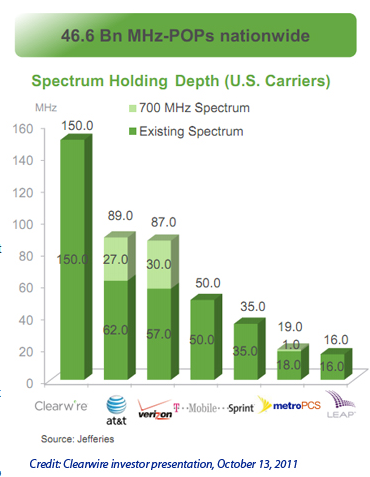

The problem, analysts argue, is that the operators that control the greatest amount of unused spectrum may be under-capitalized or unwilling to build out networks to use the spectrum. "We do not believe the U.S. faces a spectrum shortage," Jason Bazinet and Michael Rollins wrote in their Citigroup report. "Too much spectrum is controlled by companies that are not planning on rolling out services or face business and financial challenges. And of the spectrum that is being used, 90 percent of it has been allocated to existing 2G, 3G, and 3.5G wireless services by larger wireless carriers, such as AT&T, Verizon Wireless, Sprint Nextel, and T-Mobile USA.

In total, U.S. operators have licenses for about 538MHz of wireless spectrum. Only about 192MHz of that spectrum is currently being used. Most of the unused wireless spectrum is owned by companies such as Clearwire, LightSquared, and Dish Network. But so far, LightSquared has been stopped and the other companies have been slow to build networks using their available spectrum.

"There is definitely a mismatch when it comes to spectrum in the wireless industry," said Paul Gallant, an analyst with MF Global in Washington, D.C. "There are some companies that have spectrum, but they're struggling financially. Or they aren't quite sure what to do with the spectrum. And others that have the money and business model, but need the spectrum." The move to 4G is very important for these operators because it offers them a more efficient way to deliver service. 4G LTE uses the available spectrum roughly 700 percent more efficiently than the 3G wireless technology EV-DO. Carriers will soon be refarming 3G spectrum to 4G LTE in several years.

A key factor in encouraging efficient use of spectrum has been largely overlooked in carrier boardroom discussions. Wireless providers can add capacity, without obtaining more spectrum, by adding more and more cell sites. Additional cell sites in spectrum constrained areas allow the same spectrum to be used by even more consumers, as well as adding picocells and microcells to denser population areas. So far, the carriers have not expressed too much interest in this method due to additional capital expenditures and overhead. Their strategy is like what Microsoft, Apple and Google have used. It's just cheaper to buy what you need than to invest the time and energy to do the actual work.

So what can the wireless companies do? To some extent, re-farming their existing networks will help. But so will finding ways to use other spectrum. For example, only T-Mobile lets users make phone calls using Wi-Fi, yet most of the mobile devices available from carriers have this capability; the carriers just don't enable it.

Allowing Wi-Fi calling could unload millions of voice and data users on to alternative networks and ease the spectrum crunch, at least to some extent. Encouraging VoIP use would also help for two reasons. VoIP doesn't require a lot of bandwidth, and it means that the phone in question uses only the data spectrum, not both voice and data while this is going on.

These points illustrate that the carriers do have options beyond just buying up spectrum. They can offload more wireless traffic than they do now, build more cell sites into their networks and they can allow the use of other types of communications. While the spectrum crunch isn't going away, that doesn't mean that the process can't be slowed.

Sensational graphic extolling the dire spectrum crisis. Maybe a tad exaggerated???

Images courtesy: Spectrum Bridge, iqmetrix.com

Source: FierceWireless.com, Denver Post, Ecommercetimes.com, CNET

-

1

1

16 Comments

Recommended Comments